Note: This article was originally published by SmartBeijing.com and has been republished here with permission.

Graffiti in Beijing is a popular topic of late. Local filmmaker Lance Crayon’s 2012 documentary Spray Paint Beijing covers it from the ground up, capturing an incipient moment of Beijing graffiti culture’s first flowering in a way close to what seminal 1983 doc Style Wars did for the New York City subway bomber set. Last month, Liz Tung did a great piece for Time Out Beijing documenting that massive graffiti wall out in 798 and its chief protagonists: the ABS crew and its frontrunner, And-C, who also runs “the country’s first and, so far only, art supply shop dedicated to graffiti.” There has been a spate of articles more or less covering the same ground, re-establishing what Crayon does in his film: the graffiti scene here is small, it doesn’t have many places to thrive, it’s not especially well capitalized, but it also doesn’t provoke harsh penalties. So the conclusion is the standard lukewarm China-angle soft news line: it’s the same, but different.

I’m not going to re-tread that ground, and I’m not going to get into whether or not graffiti is “art” because I don’t really give a shit. Of course you can go to 798, a government-sanctioned commercial art center, and see dazzling graffiti murals. What I find more interesting in Beijing is the concept of “writing,” of signifying. A graffito is an index of urban interaction: the artist integrating his or her symbol into the visual texture of the city and inciting reactions ranging from indifference to admiration, to vexation, and ultimately to iconoclasm. Art as agency

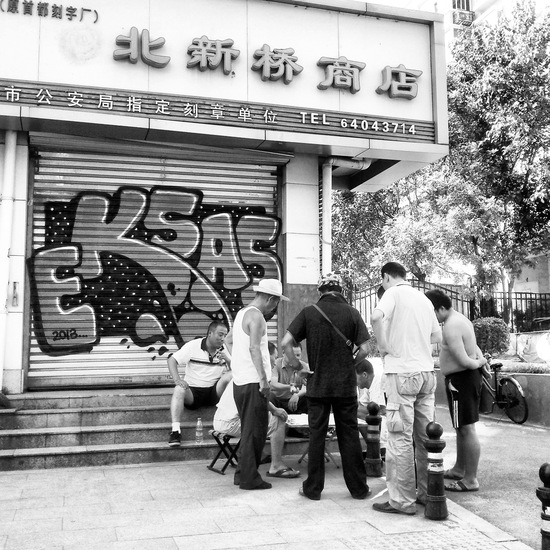

For this article, I interviewed two of Beijing’s most ubiquitous bombers: Zato and Eksas. Both have done exquisite polychrome murals — including on that aforementioned 798 megalith — but that’s not why I wanted to talk to them. It’s because they’re everywhere. You’re probably already familiar with those names. If not, now that you’ve seen them, you can’t un-see them. You can’t spit within the second ring without hitting them. Zato and Eksas exist in the interstices, the peripheries. They’re on storefront roll-down gates, construction site walls, metal electricity boxes, newsstands, mobile food carts, rooftops, underpasses, the bottoms of stairs. They are inside Beijing’s cracks.

Zato and Eksas’ tags, though to be found in virtually every corner of the city, seem to be most densely concentrated in the area between Gulou and Yonghegong to the north and Dongsi to the south. No coincidence: this is the center of Beijing youth culture, and a preeminent zone of flux as Beijing rushes to “renovate” and “revitalize” — in a word, to re-contextualize — its architectural history. Eksas, a native Beijinger who began his graffiti career at age 2 by scrawling all over his parents’ phone book, says he prefers to tag in the older parts of inner Beijing and residential zones because he likes the feeling of old constructions. It’s a poignant choice. When you tag a hutong wall, you’re not worried as much that your piece will be taken down as you’re worried the entire structure — the frame and canvas, the gallery itself — will be destroyed by the thrum of incessant inner city “development.

Ephemerality is of course a theme here. Some pieces get taken down just as quickly as they’re thrown up. They exist only in memory, or perhaps on some anonymous tourist’s smartphone. Some pieces are half removed. Some only come out at night. In fact, the best time to go graffiti walking in Beijing is dusk. As the sun sets and shop owners pull down their storefront roll-downs, an ad hoc night street gallery opens.

The store proprietors don’t really seem to mind. I walked by the building above as two middle-aged women were closing up shop for the day and asked what they thought of the rather dominating, frame-busting piece. They said, “Hai keyi.” Neither Zato nor Eksas has had much problem with police or angry tenants. As with so many other underground art scenes in Beijing, the problem is lack of interest, not open confrontation.

What Eksas and Zato do is penetrate: they switch style, scale, spelling, script, language, medium, and palette to adapt to Beijing’s shifting public canvas. The ultimate goal is to attain a kind of permanence-in-flux. To do this they follow traditional graffiti codes, but also take cues from Beijing’s original bombers: the guerrilla agents who plaster streets and apartment staircases with business-card-sized sticker ads. The net result is, again, ubiquity, a self-made place in Beijing’s literal and cultural architecture. An index of infiltration.

Below I’ll post my interviews with Eksas and Zato in full. I also snapped a ton of flicks of street pieces between Gulou/Yonghegong/Dongsi — there is nothing more anonymous in this city than a street photographer.

SmartBeijing: Where are you from originally? How long have you been doing graffiti?

ZATO: I’m from another dimension and started doing graffiti when I came to Earth. I’ve been doing graffiti long enough to know better. There are Zato tags in other cities.

EKSAS: When I was two I tagged the phone book in my house, haha. Beijing is my hometown.

SmBj: Where does your name come from?

ZATO: It’s a rough translation of my inter-dimensional name. Also I like the letters. And I dig Zatoichi, the blind swordsman. 杂投 is just a phonetic equivalent of “Zato.” I mainly write 杂投 because I like the way it looks. Sometimes I write other variants, but usually I stick to those characters.

EKSAS: I’ve tested many names. Me and my crewmate started out writing in Chinese. His tag is “疯奇” (roughly translated “funky”). I chose “灵丹” (means “panacea” in Chinese, but also means “soul”) to be my tag, haha. We really love early funk, soul, disco music, and really fun things. EXAS is actually me dismantling “灵丹,” these two words — simplifying my alphabet.

SmBj: This is the obvious question, bear with me… How do you go about tagging in Beijing? You have some pretty elaborate pieces in some pretty high-trafficked spots… Have you ever had trouble with cops or bao an or anything? Any local rubberneckers?

EKSAS: We haven’t had a big problem because we keep our eyes wide open…

ZATO: Writing graffiti in Beijing is actually pretty easy. Most people just don’t care about it. The upside of this is that no one freaks out if they see you painting, but the downside is that no one pays much attention to what you put on the wall.

From what I understand, people in places like America tend to get really angry because they think of graffiti as a gang thing or a symbol of societal decline, but in China graffiti doesn’t have any of those implications. Most people are just curious when they see me paint, a lot of times they ask me what it means or simply watch me paint for a bit.

The police haven’t given me much trouble yet. I’ve had more problems with building owners or security guards. As long as you keep an eye out and stop painting when the police roll by you’ll probably be okay. They don’t seem too worried about people spray painting their nicknames onto things.

SmBj: You seem to cover a lot of ground. What do you consider your core territory? How far out have you gone?

ZATO: My core territory is anywhere I can write my name and get attention. I’ve got some stuff out past the fifth and fourth ring roads, but not too much.

EKSAS: In old parts of inner Beijing, I’d say, or places where ordinary people live. Because I like the feeling of old constructions, old buildings. In the noisy downtown/city center areas the feeling is really great. The farthest spot I don’t really remember… maybe it’s in the outer suburbs, somewhere like Shidu.

SmBj: What are your personal favorite pieces?

EKSAS: I get bored with my own stuff. Sometimes when I just finish a piece I like it, but then a little bit later it becomes tedious and I get fed up with it. So I need to constantly explore new things to satisfy myself. A lot of my work has already been wiped off or taken down.

ZATO: Probably my favorite spot in Beijing is the the rooftop I did with Exas. I’m also fond of some of the stuff on line 13 between Dongzhimen and Wudaokou. The drinking-themed ones you mention [below] are okay too, and I like the roll-down I did with Exas and Wreck. Also writing “没有意义” on things is fun. Some of my favorites have been buffed though, like a “wild party” themed piece I did on [redacted] and one that said “I don’t have a past, I don’t have a future” in Chinese by Gulou station.

SmBj: What are your artistic and cultural influences?

EKSAS: My favorite work of contemporary art is Cloud Gate in Chicago Millennium Park. Among Chinese artists, I really like Song Dong (宋东), Zhan Wang (展望), Sui Jianguo (隋建国), etc. Song Dong’s work is really awesome, I feel he really has talent! Zhang Wang’s rock garden series and Sui Jianguo’s blind man statue series I both really like. I’m also really interested in Japanese culture, because in it I can see China’s past and future.

ZATO: Well, obviously a lot of other graffiti, both here and elsewhere. Especially early New York subway graffiti, Revs and Cost, Os Gêmeos, Brazilian Pixação, PAL crew, Twist, Espo, the list could go on. I’m also influenced by a lot of stuff outside of graffiti. I decided to do really rudimentary characters and visually flatten out some of my graffiti pieces after looking at a lot of mid-century commercial modernism (like UPA cartoons or S. Neil Fujita) as well as Futurist and Constructivist stuff (particularly Rodchenko and Malevich). Comics and movies have also given me a lot of inspiration to go out and paint. The whole DIY punk rock, get sloppy and fuck it all up ethos is also important.

SmBj: What other graffiti writers in Beijing do you like?

ZATO: The graff scene in Beijing is small, but there are definitely some good writers here. As you noticed, I like Exas’s graffiti, sometimes we paint together. Exas, Wreck, and the rest of KTS all put in good work. ABS crew is another local crew that’s quite skilled. Zak and BJPZ have some very nice stuff and are some of the OGs of the Beijing graffiti scene. Other writers like Zyko and Sbam are currently doing good stuff too.

EKSAS: Beijing’s really big, but the number of graffiti writers is pathetically small. In Beijing the graffiti scene is really lonely. I really like Feng Ji (疯奇), he’s the best guy writing in Chinese characters that I know of. Then there’s Wreck and Aigor, they’re my good friends and they’ve also influenced me a lot. And of course there’s Zato. I really admire Zato, ha. The most important thing is, these people really genuinely love graffiti. I hope everyone stays safe.

SmBj: I read before that Beijing is the center for graffiti in China. Why is that? Why do people from other parts of the country move to Beijing to do graffiti?

EKSAS: You can only say that Beijing is one of China’s art centers, probably because Beijing has a really strong nature of inclusiveness. Acceptance of new things is relatively high here.

SmBj: A friend of mine wants me to ask about “Zato’s rules.” What rules do you have, besides not letting other people cover your tags?

ZATO: The basic rules of graffiti are essentially that you can cover tags with throw-ups (simpler bubble letters) and throw-ups with pieces (more complex stuff). If you cover someone else you need to do something bigger and better. On a personal level I try to avoid painting on places of worship, people’s houses, historical buildings, murals, or nice pieces of architecture. On the other hand, ugly generic box buildings or dull gray roll-down gates are totally fair game.

SmBj: In other parts of the world, graffiti culture is very closely connected to underground music culture. What kind of music do you like? Do you go to a lot of live shows in Beijing?

EKSAS: I like practically every style of music. I change the music I listen to based on the season. This winter I’m listening to a lot of soundscapes, stuff like Akira Kosemura‘s music. I’ll also go check out Beijing’s underground music scene. Purple Soul (龙胆紫) is a Beijing underground hip hop band that I really like.

SmBj: Zato – how important is text in your work? I ask because I’ve noticed you have some “twin” pieces, like “Drunx not Dead” near Zhangzi Zhong Lu and “好酒不见” near Gulou. How do you think your work resonates differently in English vs. Chinese?

ZATO: I enjoy throwing in some connected phrases when I’m doing characters or letters. I’ve also done some work here that’s just large bubble letter messages. People are more likely to notice something with a message they can read and try to puzzle out, it might add a bit of mystery or special meaning for them.

I think doing things in Chinese stands out a bit more because there aren’t many people doing Chinese graffiti. It’s also more accessible for most people in Beijing, even if using English is more international. I want to be able to reach people who otherwise might not pay any attention to these kind of things.

SmBj: Eksas – Sometimes you write your name EKSAS and sometimes EXAS — why use different spellings?

EKSAS: Because the space on a given wall or shutter door is variable, I have to change the length of my name to match.

SmBj: I saw recently that you’ve been making EXAS

stickers and posting those around town. Why did you start making

stickers? How is throwing an EXAS sticker up different from doing an

EXAS tag?

EKSAS: Your sight is really keen. It’s because we admire the guys

who post up those tiny advertisements, no matter where you go you can

always find them. Even though they’re not graffiti, they enlightened us.

It’s only a difference in scale, large vs small. [With these stickers] I

can infiltrate (“渗透”) more nooks of the city.

***

Graffiti is free and open daily (/nightly) to the public. Go outside

and use your eyes. Best walking galleries at this writing are Gulou Dong

Dajie (south side of the street), Andingmen Nei Dajie (west side of the

street), Zhangzi Zhong Lu (mainly the strip across from Yugong Yishan),

and Dongsi (though those ones are going fast).